by Ben Best

My prime motivation for going to China in July, 2004 was to attend the annual Society for Cryobiology Conference in Beijing. Aside from my desire to learn more cryobiology, I had hopes of meeting Chinese cryobiologists with an interest in cryonics.

|

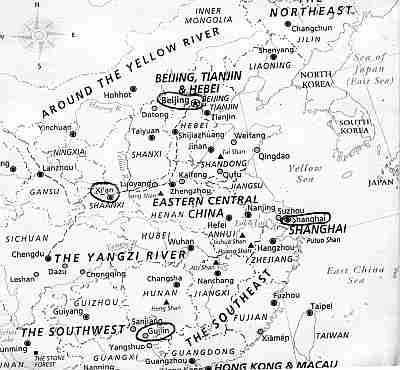

The conference organizers offered group tours for those in the conference who wanted to spend a week after the conference sightseeing in China. I chose the tour which offered the greatest geographical diversity — one that would take me to Xian, Guilin and Shanghai after Beijing. I also looked forward to the opportunity the tour would provide to get acquainted with cryobiologists and to learn some cryobiology while learning about China.

Despite repeated e-mail exchanges with the tour organizers, I never got a straight answer about the exact start time/date and end time/date of the tour. I thought it may have been a language problem, but I now suspect that the organizers wanted to maintain flexible options for themselves. This made it difficult to decide on flight times and was enough to dissuade many people attending the conference from going on an after-conference tour. I booked my flights to give me a few days before the conference and a few days after the tour — which would allow me to do some of my own sightseeing, as well as providing security about dates and times.

Tours are valuable insofar as the organizers have the knowledge to simplify logistics and get you to the prime sights at the best times. The down-side is that you spend too much or too little time at the sights, see things that aren't of interest and miss things that are of interest. It was not legal or possible to rent a car in China, but I feel pleased that I was able to have a good complement of tour sight-seeing with sight-seeing on my own.

Getting a visa for China is not trivial. It is not possible to enter China with a passport that expires within six months of the entry date. To get a visa requires surrendering your passport to a Chinese Consulate for five business days along with a new passport photo, a fee and a form giving personal details and details about the journey.

I did more preparation for my trip to China than for any trip I have ever made. I read several histories of China and have written a A Simplified History of China for my website, which gives the essentials to make the sights more comprehensible. The best cassette language course I found was Barron's GETTING BY IN CHINESE. I used the book TEACH ™ YOURSELF BEGINNER'S CHINESE SCRIPT to compile about a hundred index cards with Chinese characters I tried to learn. I also read through several travel guidebooks.

I was very worried about money, partly because of some very bad advice I had gotten from someone who had recently returned from China who told me that travelers' checks & credit cards are of little use and that I should take a lot of American hundred dollar bills. The tour organizers had made no arrangements for prepayment, which meant I had to ensure that I took enough money to cover the tour as well as all my other expenses. I was not comfortable carrying lots of cash. I decided to take a couple of hundreds, some twenties, about 50 ones and US$1,200 in travelers' checks along with my credit card — which I would carry in a money belt along with my passport. (It is not possible to obtain Chinese currency outside of China.) I figured that I would have enough access to major hotels and big banks in the big cities that I could cash the travelers' checks when needed.

Money & prices play a much larger role in my description of my trip to China than they do in previous travelogues I have written. The Chinese are a very shrewd & commerically-minded people. There is a huge difference between Western prices and Chinese prices. Chinese have much more knowledge of the difference between Western and Chinese prices than Westerners do. It is easy for Westerners to pay Western prices and Chinese have a powerful incentive to induce Westerners to pay those prices rather than Chinese prices. So the traveler who hopes to benefit from Chinese prices has a big challenge to learn what those prices are and to be constantly alert to avoid being duped into paying more. Awareness of prices & barter, I decided, was an important part of learning about Chinese culture and about the interface between Chinese and Western societies. (Barter is an irritant for those interested in quick transactions. For most Westerners, the only experience they have with barter is in buying or selling a house or car.)

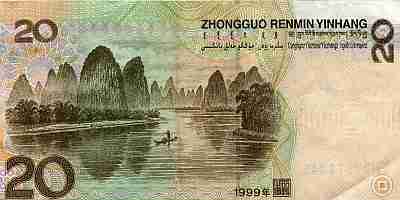

The official name of Chinese money is "People's Currency" — Renminbi, RMB. Only once in China did I hear anyone call Chinese money Renminbi — a hotel clerk. Prices were always quoted in Yuan, which can be represented by the symbol ¥ (the same symbol used for Japanese Yen). The exchange-rate for the Yuan was roughly 8.3 Yuan per US Dollar, but my simple-mind found it easier to shift the decimal place to the left one digit when I wanted a quick conversion. Thus, in my mind ¥100 was $10.

I arrived in the Beijing airport at 3pm on Monday, July 12, 2004 after an 11-hour flight from Vancouver, Canada that added a day crossing the International Dateline. My priorities were to get some Chinese currency, to get a Beijing city map and to get to my hotel. I saw an office identified in big English letters as a Tourist Bureau. They had no maps or tourist information of any kind and seemed only concerned with selling hotel rooms & ¥380 rides to city hotels. My guidebook had said that a taxi from the airport should not cost more than $8, so I declined. I was able to get ¥1,000 from an ATM with my Visa credit-card and I bought a bilingual city map at an airport bookstore.

I was approached by a fellow with a laminated taxi-card who wanted to take me to my hotel. On the back of the card were a number of prices from the airport, the lowest being ¥380. I tried to walk to where the taxis were parked (with the first man still following) when I was approached by two more men with laminated taxi cards that showed the same prices printed on the back. Out of misplaced loyalty I agreed to go with the first man for ¥380. I later talked to others attending the conference, one of whom told me everyone had paid ¥380 and another of whom said she had argued the drivers down to ¥200, but knew of others who paid ¥100.

I was escorted to a car downstairs in the parking garage. It was a nice car, but it wasn't a taxi. Another man was the driver. My mind wasn't functioning at full throttle, so I put my luggage in the trunk and got in. As we drove from the airport and I saw another passenger being driven by a clearly-identified taxicab, I started thinking how I had made myself vulnerable to being abducted and robbed. As we approached the toll gate the driver asked me for ¥100 to pay the toll. I handed the driver a red ¥100 bill and later watched him hand a green bill to the toll booth operator. I believe the toll price is ¥10. The driver did not drive into the hotel, but stopped well before the entrance. I argued with him to give me my luggage from the trunk before I would pay, but his English was limited and I finally paid him. He removed my luggage from the trunk and I walked to the hotel feeling thankful that my foolishness had not caused me to be robbed.

I was staying in the Beijing Continental Grand Hotel, adjacent to the International Convention Center where the cryobiology conference was being held. Unfortunately, the hotel is far north of the city center (just south of the site of the 2008 Olympics) and far from the nearest subway station. Beijing has four large concentric Ring Roads (superhighways) and my hotel was north of the Fourth Ring Road.

Although bicycles are still common, automobiles and buses are the prominent form of traffic. I was told that 15-20% of families in Beijing have a car, up from only about 5% only a few years earlier — which show how fast things are changing in China. Many people ride buses, subways or ride motorized bicycles rather than standard bicycles. There are no bicycle lanes on the superhighways, but major streets typically have wide bicycle lanes on each side — which are not crowded with bicycles. Traffic lights and pedestrian crossings on streets are few and far between, but pedestrian walkways under & over streets are common. Jaywalking is also common.

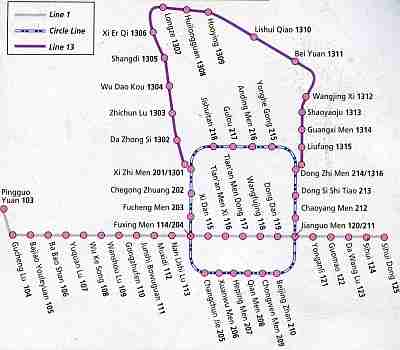

I walked for nearly an hour-and-a-half in the southeasterly direction, soaking up the

ambience of Beijing streets, buildings and traffic. I saw horses, pedicabs, cars parked

on sidewalks and all manner of transport on the sidestreets. Feeling that I had done

enough walking and feeling that I wanted to get downtown (and learn the subway

system), I headed for the Liufang (1315) subway station and bought tickets to

take me to Tienanmen Square for ¥5. The Beijing subway system is more

complicated than the Shanghai subway, and I never did completely figure it out.

Transferring from line 13 to the circle line seems to involve paper tickets which are

hand-checked and torn, whereas the other lines only involve machine-readable tickets

that are used in turnstyles for entry & exit.

|

Tienanmen Square is the largest public square in the world — the size of 90 American football fields. It was filled with soccer-players, kite-flyers and lots and lots of people who were just walking about. I was approached continuously by people trying to sell me things, including kites, and I rebuffed them all. A few had mentioned art exhibitions. I was beginning to feel like I was being excessively unfriendly, so when a couple of young women told me they were students wanting to practice English I stopped to chat with them. They said they were students of art & calligraphy and invited me to look at their work.

They lead me to the Museums of History/Revolution which they told me was China's major Art Museum. They had to show a pass to a soldier before we could enter the small gallery. I was given a cup of jasmine tea and shown some calligraphy/art. Many Chinese characters are like pictograms and alterations of these characters partially resemble other characters or objects to form a kind of visual poetry. Two screens each showed 100 characters — one for the word "happiness" and another for the word "longevity", two key words/concepts/aspirations in Chinese culture. A number of pictures showed the same scenery in each of the four seasons, a common Chinese artistic device. Spring is youth, Fall is maturity and Winter is old age. There were two birds in every painting one of the woman had made — two birds she said "would never leave each other". It was a nice presentation and I probably overreacted when they tried selling me their art for ¥100, but I did leave then. I was approached by many more art/calligraphy students wanting to practice English, but I did not go to look at more art.

I dropped into a few shops on the east side of Tienanmen Square and bought a large bottle of water for ¥5 along with some odd foods for which I probably overpaid. I walked along the southern curve of the semicircular street south of Tienanmen — an area known by the name of the south gate — "Qian Men". Just south of this area are the streets & alleys known as "silk streets" (or Silk Alley). Little silk is sold there, but the area has the best reputation in Beijing for good prices & bargaining on low cost items. I was pleased to find a 7/11 store in the semi-circle — pleased to find listed prices that relieved me of haggling.

I waved a taxi off the street. When I showed the driver the hotel where I was going, he held up four fingers to indicate that he would take me there for that price without metering the trip. I complied, despite the fact that I had never given an unmetered trip in my years of driving a taxi. It was a long drive to the hotel, one which would have cost me at least $30 in Toronto. The driver stopped short of the hotel entrance and asked for payment. When I handed him ¥4 he had a conniption and drew "40" on his palm. Because I had no other change I was forced to give him a ¥100 note. When he only gave me ¥10 in change, the language barrier suddenly became insuperable, and I could not induce him to give me more change. Finally, I got out of the taxi in a state of frustration.

From the point of view of Western prices, I should not have been upset. But from

the point of view of being cheated & deceived, I was extremely irritated. I took the

same trip from the south end of Tienanmen to the hotel by taxi several times afterwards

and the trip was always metered, the drivers always came right to the front door of the

hotel, I never paid more than ¥35 and I always gave a generous tip. (Until

recently, service people in China were forbidden from accepting tips, but that is changing

rapidly, like so many other things.)

|

I went to the hotel desk and made arrangements to have a city bus tour the next day. I am a great fan of such tours as a way of being introduced to a city, but it turned out to be only a tour of Beijing's three biggest tourist attractions rather than what I would call a city tour. The big three are: the Summer Palace, the Temple of Heaven and the Forbidden City.

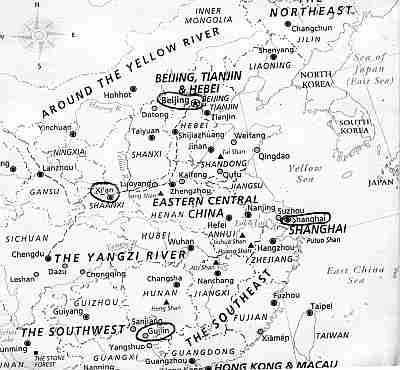

Tuesday morning I was on a bus with occidental tourists heading to the

Summer Palace, which consists of an entirely artificial lake & island

in the northeastern corner of Beijing. Kunming Lake was named after a lake in Xian

and the elevation on the island is called Longevity Hill (Wanshoushan). The Long

Gallery is the longest painted corridor in the world, and it runs along the south

edge of the island (facing Kunming Lake). I can

understand why the emperors liked to spend their summers there because the

breezes off the lake were a welcome relief from the humid heat of Beijing. Like

so many constructions I saw in China, the Summer Palace is a testament to

the inexhaustible self-indulgence of the emperors and the vast labor pool at

their disposal.

|

In particular, the Summer Palace was the preferred residence of Empress Dowager Cixi, who ruled China for most of the last half of the 19th century. She had enormous banquets which consisted of foods to look at, foods to smell and foods to eat. (The name "Cixi" is written in Pinyin, a means of representing Chinese sounds with Latin letters. But all the Pinyin Latin letters are not pronounced as an English-speaking person might expect, and "Cixi" is a good example of the divergence because it is pronounced "Tsisyi".)

The Long Gallery has intricate portraits at every step, which may have been a rich source

of entertainment in the age before moving pictures. On the north side of the corridor I saw

many examples of what appeared to me to be volcanic rock mounted on pedestals where I normally

would expect statues. (Which is not to say that the rocks lacked artistic merit.)

|

Aside from our tour group of occidentals, overwhelmingly the other tourists were Chinese — which proved to be the norm for almost every tourist attraction I saw in China. At the end of the lakefront was a construction made entirely of Marble, built so as to extend into the lake like a floating boat. Just east of the marble boat we boarded a "real" boat which took us across the lake to the eastern shore.

As often happens on tours, we were taken to a shop — in this case a Pearl

Market where we were given ample time to shop. In a demonstration, an

oyster was opened which had 25-30 tiny pearls — too small for the pearls in

a necklace. We were each given a sample. While I was waiting for the shopping

period to end, I spoke to our tour guide about the one-child policy in China. She

told me that an urban couple can have two children only if they were both an only

child of their parents. An unauthorized extra child would mean large fines (someone

told me ten times annual income) and the loss of a job, if employed by the government.

The urge of most Chinese is to have as many children as possible, so it is somewhat

ironic that China has a one-child policy. Someone told me that she believes the

one-child policy is why China has experience rapid growth, whereas India and

Indonesia have not. Another tour guide told us that the Chinese devotion of parents

to their children combined with the one-child policy has led to children being treated

like little "princes" & "princesses" (a nation of "spoiled"

children?).

|

We were taken to the Temple of Heaven, a large park in the southern section of Beijing where the emperors went for rites, sacrifices & prayer. The Chinese conception of Heaven & Hell is unrelated to Buddhism, Taoism or Confucianism and does not seem to be based on written scripture. The Chinese use the same word (tian) for "day", "heaven" & "sky". The emperor was the son of Heaven and was to be revered as a link between Man, Heaven & Nature. Not much was said about the parental nature of Heaven, but a pleasant afterlife in Heaven or a tormented afterlife in Hell was the reward or punishment of life on earth. These were ancient beliefs that few currently believe. Most contemporary Chinese have no religion, although superstition is widespread. Among young, urban Chinese, Christianity is the most popular and fastest-growing religion. Buddhism is still the most widely believed religion among believers — especially among the elderly.

The outer portions of the vast Temple of Heaven park consist of well-kept grass

with trees of uniform size which are evenly spaced in a regular grid of rows &

columns. Our group had a lunch at one of the pavilions. Like so many Chinese

meals I was to have, our group sat at a circular table with the selections placed

on a wheel in the middle of the table. Chopsticks often took food directly into the

mouth, which seemed somewhat unsanitary for a city so recently stricken by SARS.

My companions were mostly Swedes, except for a young Florida couple who had taken jobs

teaching in central China immediately after graduating from university. The Swedes had come

via the trans-Siberian railway. They were impressed by the vast grassy deserts of the Gobi,

which has a landscape very unlike that of Sweden.

|

The most noteworthy landmark in the Temple of Heaven is the Hall of Prayer

for Good Harvests, which is a signature piece of Chinese Imperial architecture

often used as an emblem of Beijing. The building does not contain a single nail.

Our tour guide told us to meet on the other side of the Temple in half-an-hour. I

wandered off, thinking that she meant the north gate. Twenty-five minutes later, finding

no one at the north gate, I panicked and ran down the Sacred Way to the south, and then

ran back and finally made my way to the east gate just as the bus was preparing to depart

without me.

|

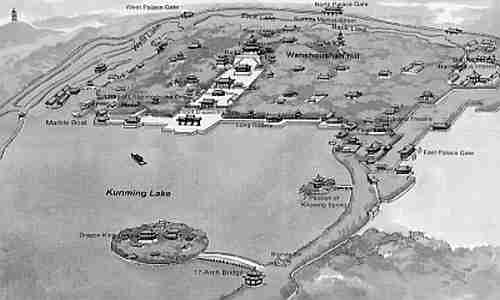

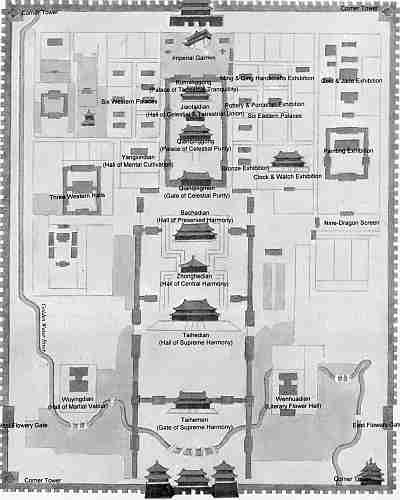

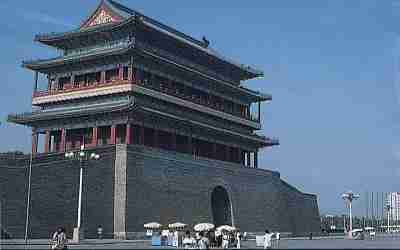

The Forbidden City is described as the largest museum in China. As the number one tourist attraction in Beijing, I was somewhat irked that the tour company had allocated only two hours to see it all. After having seen it for two hours, however, I had no desire to see more. We began by crossing Tienanmen Square.

Tienanmen Square is the "front yard" of the Forbidden City. "Tienanmen" is Chinese for "Gate of Heavenly Peace". Our tour guide described some of the demonstrations that have occurred in the Square during the 20th century, but glossed-over the 1989 student protests. No one asked her about the incident, and I heard no other mention of it during my time in China.

Small groups of soldiers marched seemingly haphazardly through the

Square, amongst the milling throngs who parted to make way for the formations.

I would see individual soldiers standing guard throughout the city — in front of

department stores, hotels and in seemingly arbitrary locations around parks.

A few were like Buckingham Palace guards at the gates of the Forbidden City.

I was impressed by the extreme slenderness of most of the soldiers

(impressive to someone who aspires to practice CRAN,

Caloric Restriction with

Adequate Nutrition). But I was also aware that their slenderness made the

soldiers appear less threatening.

|

The Forbidden City was the Imperial Palace of the Emperors of the Ming & Ching Dynasties, a palace forbidden to all but a privileged few. The inner portions of the palace were forbidden to all but the emperor, his concubines and his eunuchs (and sometimes his empress). As our tour guide described it, the emperor was the only "gentleman" allowed on the premises. She described eunuchs as "men with deleted function". The position of the empress did not seem particularly privileged. After death of a Ching emperor a ceremony was held in an inner courtyard in which it was announced which child of which concubine the deceased emperor had selected to be the next emperor.

Our tour group took what is called the "middle route" — right

through the center of the Forbidden City. I could be impressed by the scope

of the construction, but the halls, gates & courtyards all looked alike to

me. See one and you have seen them all. The names were more charming

to me than the buildings — Gate of Heavenly Purity, Hall of Everlasting Spring,

Hall of Cherishing Essence and Hall of Joyful Longevity. We would go through

one courtyard, crowd up against a building we were not allowed to enter and

try to peer inside. Then we would proceed to the next courtyard and repeat

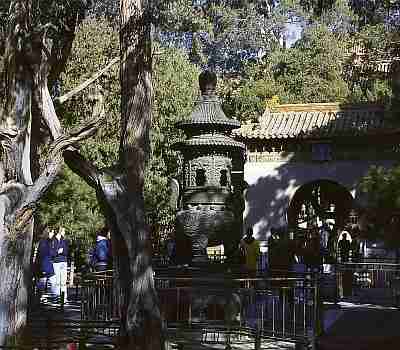

the process. After many iterations we finally reached the Imperial Gardens,

a garden of mostly rocks & trees which I found beautiful & interesting.

But by then we only had ten minutes before the Forbidden City closed for the day.

|

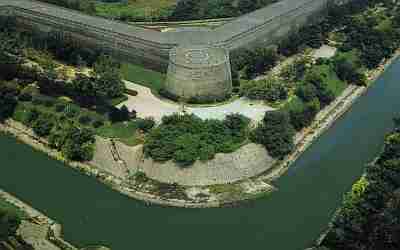

I parted company from the tour group and headed northeast along

the moat. I watched people fishing in the moat and I contemplated the fate

of those who may have been foolish enough to attempt swimming the moat

and scaling the walls of the Forbidden City. When crossing the streets

I tried to stay in the middle of groups of pedestrians, who were probably

more street-wise than I (and who would be hit before me if I stayed in

the middle).

|

I paid a ¥10 admission fee to the Beihai Park, which is actually

an extension of the Imperial Gardens containing a man-made lake. The

beauty of the park on the south end of the White Dagoda island rivals that of

the Imperial Gardens, which compensated me for only being able to spend

ten minutes there. Scaling the steep steps on the hill of the

White Dagoba (a Nepalese-style pagoda) gave me some much-needed aerobic exercise.

The view of the city from the top was excellent, but the Dagoba looks pretty drab up-close.

|

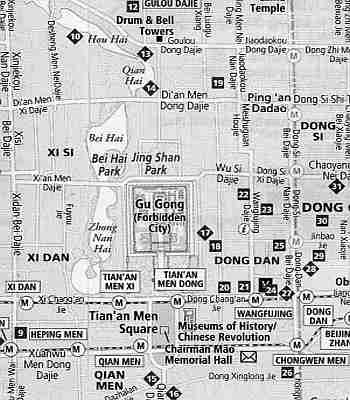

For orientation, I offer a map of downtown Beijing and a short table of words that occur repeatedly in Chinese street names:

| Pinyin | English | |

|---|---|---|

| Bei | North | |

| Nan | South | |

| Dong | East | |

| Xi | West | |

| Jie | Street | |

| Dajie | Avenue | |

| Lu | Road | |

| Men | Gate |

(Note that "Beijing" is "North Capitol", "Nanjing"

is "South Capitol" and "Xian" is "Western Peace".)

|

Exiting the north end of the park I headed for the Drum Tower/Qianhai Hutong area. Hutongs (Lanes) are a reputedly culturally-significant aspect of Beijing which are rapidly disappearing to make space for highways, apartment houses and modern buildings. At one time Beijing was primarily a huge maze of these short, narrow alleyways that surrounded quadrangle family residences (where parents lived on one end, male children on the side and female children behind the back side of the courtyard).

Exploring the area I mostly saw gray, drab short alleys with many twists & turns. I saw some gatherings of people smoking & playing board games or doing bicycle & car repair. I did not feel comfortable being so alone and vulnerable walking these alleys, so I was glad when I emerged into a market area.

I was feeling somewhat confused about what my next move would be when I was accosted by a very aggressive pedicab driver. I kept trying to get away from him, but I finally relented and decided he might be able to give me a view of the hutongs I had missed. We agreed on a price of ¥100, but after driving me about 20 feet he stopped the vehicle and showed me his itinerary, pointing-out the printed price of ¥180. I got out of the pedicab, but he protested and after some haggling agreed on ¥120. I was irritated at having conceded the extra ¥20 in light of the original agreement, but not irritated enough to terminate the trip or argue further.

We covered a lot of territory pretty quickly in the pedicab, but with my money-belt full of cash, traveler's checks and my passport I started getting nervous about my vulnerability to being robbed, which undermined my enjoyment of the sightseeing. I was reluctant to venture into the compounds he took me to, despite the fact that they might have given me more insight into hutong life. When we returned to where he had picked me up I paid him ¥120, but did not give him the tip he requested.

I walked along the market area looking at the foods for sale. I wasn't feeling adventurous enough to buy some of the most unusual (and unappetizing) looking foods and decided to buy some fruit. With some haggling I was able to get peaches for ¥1, pears for ¥2 and apples for ¥5, but the woman at the fruit stand was intransigent about ¥10 for oranges. I finally relented, buying oranges at her price. Then I took a metered taxi-ride back to the hotel.

I was able to get Yuan cash advances off my Visa credit card from my hotel ATM machine (Agricultural Bank of China), which relieved some of my cash worries. I typically took ¥1,000 at a time. I was out of water so I was forced to buy a large bottle of Evian for ¥32 at the hotel shop (rather than the ¥5 I would pay for an equivalent Chinese bottle of water downtown). Even in the four star hotels I stayed-at in China the tapwater is unfit to drink. I needed bottled water to brush my teeth and for the second wash of my fruit. Fortunately, bathrooms had special sockets adapted to Western shavers.

The next morning I decided to head down to Beijing's number one shopping street, Wangfujing Dajie. I had first thought that I should take a taxi to the subway, but then decided that by leaving at 9:30am I would miss rush hour and could take a taxi all the way. My first instinct would have been better because the taxi spent a great deal of time stuck in traffic and it took me nearly and hour-and-a-half to get to Wangfujing. It did give me the opportunity to notice driving patterns along with more scenery than I could see from the subway. During all my time in China I only twice saw motorized traffic police — two motorcycle cops in Beijing and two in Shanghai. On both occasions the two were together. I saw driving patterns I have never seen anywhere else. On this occasion I saw an entire line of cars driving across the on-ramp to a highway — and my taxi was one of them. China may be a police state, but there is anarchy on the roads.

Much of Wangfujing is a pedestrian mall where no cars are allowed. It was crammed with people, but only rarely did I see occidentals — despite the fact that I would expect this to be a tourist mecca. (The Forbidden City is a tourist mecca also, but the tourists are overwhelmingly Chinese.) Despite being the only occidental in sight, most of the time I did not feel I was conspicuous or even noticed.

Chinese sometimes call foreigners "big noses", but I'm not sure that this has the same significance as "slant-eyes" to some Westerners. If there was any racist feeling against me (and there must have been some) I did not notice it. Except for occasionally being made to feel insignificant when Chinese pushed ahead of me in line and clerks (civil servants selling subway tickets) happily gave priority to the Chinese. For the Chinese, race & national pride are easily co-mingled, which can make the distinctions between racism & patriotism somewhat fuzzy.

In one sense, though, my occidental character was conspicuous, because I was repeatedly approached by women individually or in pairs — less often a male/female couple or lone male — who said they were students of art & calligraphy who wanted to practice English and who wanted me to see their art. Only on Wangfujing and Tienanmen Square was I approached by these "students". I had the thought that my initial experience had been interesting and that I should try seeing some more art, but I never did.

Of special interest to me was the Wangfujing Bookstore, which is easily as big as the so-called "World's Biggest Bookstore" in Toronto. Almost every book in the store had a title in English along with the Chinese, despite the fact that the rest of the book would be entirely Chinese characters. Somehow I had gotten the impression that pinyin — Chinese written in Latin rather than Chinese characters — was an alternate writing system for modern China. Only in the bookstore did I come to realize that pinyin is only used for street signs and to help foreigners learn Chinese. All Chinese books are written in the graphical Chinese script. Even Chinese computers are designed to handle Chinese script rather than pinyin.

I did find a few English language books. I bought some more guidebooks at very low prices and even found a molecular biology book (published by John Wiley & Sons for a Chinese market) for ¥65 — less than a tenth what I would pay for the same book in North America.

I visited department stores, medicine shops, clothing stores, etc., doing a bit of haggling and buying. There was no shortage of staff in most of these stores. I would see one, two or three clerks standing on every aisle or behind every counter — all waiting to serve. I suppose this is a testament to the amount of cheap labor available, but it made casual shopping & decision-making difficult when there was always a salesclerk attempting to give immediate service.

When I reached what I thought was the south end of Wangfujing I began to feel completely lost until I realized my directions were switched and I was beyond the north end. I headed down a side street and could see that I was in a shopping area that was entirely directed at Chinese. The signs were all entirely in Chinese characters except for the occasional URL (ending in .com.cn). Although these shops were heavily staffed, I was not attacked by service people when I entered them. The clerks stood by looking somewhat awkward — dumbfounded by my presence. Probably they spoke no English and had no idea how they might respond to me. On the street I saw some nice leather belts selling for ¥10 so I bought one from a fellow who wordlessly and passively responded to the transaction.

I walked south down a street between Tienanmen and Wangfujing until I

reached what appeared to be the entrance of a beautiful garden walkway. A man

was standing directly in the path, as if standing guard, but I decided to approach

anyway. In an instant he was all over me, shoving his packs of postcards in my

face and not letting me get away easily. Eventually, I did get away. Once past the

"guard" I was delighted by the 20-meter-wide garden walk, with its

streams, sculptures, bridges and tranquillity. Amazing to find so few people in

a garden so close to Tienanmen & Wangfujing. A soldier stood at the far

end of the garden walkway, but he made no response when I passed him to

enter the street.

|

I was ready to explore Beijing through the subway system, so I jumped on the Tian'an Men Dong (117) subway and made my way to Xi Zhi Men (201/1301). I went outside, walked the streets a bit and then returned for a ride to Lishui Qiao (1310) on Line 13. Subway line 13 is actually above ground, so it gave me an opportunity to do some sightseeing at the north end of the city — mostly the sights of huge apartment buildings, many under construction. On this subway — as on all lines — announcements of the next subway stop are made in Chinese and then in English. Chinese/English bilingualism is everywhere in China, which makes life much easier for the English-speaking traveler than it would be otherwise.

Lishui Qiao is a real suburban-type subway stop. There were racks and racks of bicycles locked there by commuters. The stop was also a construction site, and I had to walk through a lot of dirt to reach the street. A number of construction workers said "hello" — a word often heard by occidentals traveling in China. Here, however, it was just a friendly way of making contact with a foreigner rather than a code word for "buy this". A couple of enterprising fellows had laid blankets on the dirt where they displayed the DVDs they had for sale. At the end of the dirt road was a collection of pedicab and taxi drivers awaiting those exiting the subway. There too greeted me with a chorus of "hellos", but the intent was clearly to attract my business.

I started walking down the highway until I came to a pedestrian walkway that crossed over the highway. "Why does the tourist cross the road?" To sight-see on top of the pedestrian crossing! From the top I could see that there was nowhere I particularly wanted to go, so I went back to the subway. When I told the ticket-seller I wanted to go to Pingguo Yuan (103) — the terminus of the East/West line and the most remote from my current location — she laughed, but gave me the tickets. Perhaps she had realized that I was touring Beijing by subway.

At the subway platform there was a woman standing behind a table loaded with newspapers and magazines. Most were entirely in Chinese, but a couple were in English, notably the paper BEIJING TODAY, which I purchased.

After a long ride (standing most of the way) and several transfers, I arrived at the Gucheng Lu (104) subway stop, where everyone was told to get off the train. I never understood why. I lost interest in going to Pingguo Yuan (103) — I saw no need to make a special effort simply for the sake of getting to the end of the subway line. On the street outside the Gucheng Lu subway there was a very interesting pedestrian stoplight. In red letters it displayed the number of seconds remaining before it turned green, counting down the seconds. No one waited until zero before beginning to cross.

I walked into a department store and found a bakery section that was actually selling bread — not a common item in the Chinese diet. I wanted time to examine all the breads, but I was immediately pounced-upon by a pushy saleswoman who was encouraging me to buy the sugar-loaded breads that were more like cakes. I really wanted sugar-free whole grain bread, but she gave me no time to search — she was too much "in my face". I ended-up compromising somewhat and purchased before I was really ready to do so. As with most of the department stores, they had a Soviet-style purchasing system where the clerk writes you a receipt, you present the receipt and your payment to a cashier, and then you present the stamped receipt to the clerk in exchange for the item purchased.

I went back into the subway. I had done all the standing I could bear, so when the subway train arrived from Pingguo Yuan with some empty seats available I followed the Chinese practice of politely, but quickly, rushing for one of the available seats and succeeding in being able to sit. I arrived back at Tian'an Men Dong (117) station four-and-a-half hours after the time I began my subway expedition in that same station. I walked diagonally across Tienanmen Square (packed with people, as usual) ignoring the kite salesmen, the art students and anyone else accosting me.

Beijing was sweltering hot in July, but my hotel room was painfully cold. My attempts to adjust the thermostat were futile, insofar as it appeared to be purely ornamental. I was cursing myself for not having brought a sweatshirt to China and was unable to find sweatshirts being sold anywhere. I walked into a shop selling coats. On closer inspection I could see that the coats were mostly leather, which was not what I wanted. The sales attendant was quickly showing me a leather jacket, and she punched ¥380 into her pocket calculator and held it up for me to see (a common device for haggling between foreigners and people who speak only Chinese). When I nodded "no" she handed me the calculator to punch-in my counter-offer. I punched-in ¥144. She indicated disagreement, said the word "leather" and showed me ¥300 on her calculator. As I walked out of the store she shouted "200", but I had decided that I wasn't even interested in paying ¥144. Pretending to walk away from a counter-offer is a standard bargaining practice — and this kind of phoniness is part of what I hate about the bargaining process. Mine was not a pretend walk-away.

I went into a department store just north of Silk Alley and saw a suitable jacket with a sign on it that said ¥100. The sign disappeared when they saw me coming and they gave me an asking price of ¥380. I protested that I had seen the ¥100 sign and they eventually sold me the coat for ¥100. They shoved a shirt in my face which I liked and asked ¥40. When they threw in a matching pair of shorts for the same price, I accepted. I was feeling tired, wasn't interested in more shopping and wasn't interested in more bargaining. But I must have overpaid, because they were in a feeding-frenzy of shoving clothing in my face. And this attracted the attention of other clerks in the same area because I really had to battle my way out of this store. Many people were shouting "hello", pulling on me by my clothes, grabbing me by the arm and/or standing directly in front of me to block my path.

I found the Internet Cafe right next to the 7/11 store I had found on Monday evening — and am not sure how I could have missed it at that time. I was required to write down my country of origin and my passport number. My passport was in my money belt under my pants and I didn't want to remove my pants right there so I guessed at the passport number — and the clerk did not question me about it. I saw a higher concentration of occidentals in this Internet Cafe than anywhere else in China. There was another Internet place for Chinese in the same building and I am not sure what the differences were. I was not allowed to use the Chinese facility, which was "members only". The business center of my hotel sold Internet access for ¥2 per minute, in contrast to the ¥20 per hour I paid at this Cafe. After catching-up on my e-mail, I took a taxi back to my hotel.

In my hotel room I read-through some copies of BEIJING TODAY. I saw a number of things in those newspapers that I would not have expected in a communist country having no freedom of the press. Experimental sex education programs were being started in some schools partly because too many children were learning about sex from pornographic websites. Some Beijing taxi drivers were demanding that private taxi firms be allowed. Citizens were protesting the demolition of "historic" homes & hutongs by the Beijing municipal government which was widening a street. There was a report on a woman whose application for In-Vitro Fertilization (IVF) was rejected by China's Ministry of Health because her husband was recently killed in a car crash and single women are prohibited from having IVF.

During the conference I did not have much success in getting to know many of the native

Chinese. Most did not speak English very well and when I sat in their groups during lunch time

I was ignored while they spoke Chinese to each other. I did once have a lunch with a

cryobiologist from Taiwan who may have been a bit of a pariah because of her country of

origin. She answered many of my questions about Chinese language & culture, including

about the Chinese Zodiac, which is a 12-year cycle of years rather than months — and which

is based on animals rather than constellations. She was born in the year of the Dragon.

Everyone tries to have children in the year of the Dragon because it is such a propitious

symbol, but she felt that it created a problem for her when competing for jobs.

|

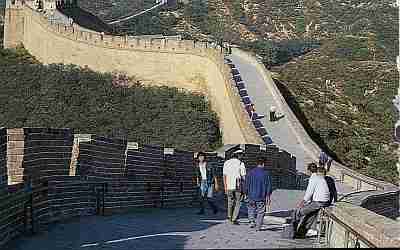

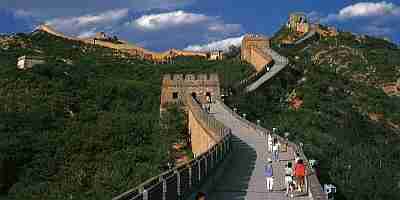

The cryobiology conference reserved an afternoon and an evening in which we were taken to the Badaling section of the Great Wall. Whenever I think of the Great Wall I remember President Richard Nixon's remark, "This is truly a great wall". My guidebook said that the claim that the Great Wall is the only man-made object that can be seen from space is a myth. (I think this claim originated before anyone went into space. Large cities are easily visible at night as points of light at low orbit. The visibility of objects from space is, naturally enough dependent upon distance.)

After posing for a group photo of everyone in the conference we were given a couple of hours

to walk along the top of the Great Wall. The Wall runs along the top of mountain ridges and the

walkway on top of the Wall — which is about as wide as the lane of a highway — can be quite

steep in places. "Climbing the Great Wall" actually means walking along the top

of the Wall toward a higher elevation. From where we were standing, the wall was an uphill

climb in both the left direction and the right direction. Because most of the people were

going to the right, I went to the left.

|

The walk was steep, but I went at a fast pace to get some of the aerobic exercise I had been missing by not having access to my gym. Periodically there were level areas where it might have been possible to enjoy the view were it not for all the merchandizers shoving packs of postcards in my face. I literally could not see the scenery for a reasonable period of time without a huckster obstructing the view. As I got higher on the Wall, however, the number of Chinese peddlers began to diminish. I did buy an "I Climbed the Great Wall" T-shirt for ¥20 after some hard haggling. Shortly after having done so, I was approached by another seller whose first asking price was ¥20, which probably means I could have gotten one for ¥10 or less.

Just as I felt I was making good time, was approaching a top and was distancing myself from the crowds I came to a dead end. The Wall was crumbled and closed-off beyond where I had reached. I later learned that I could have gone much further by initially going right rather than left.

The buses took us to a ceramics factory where we were given a demonstration of the intricate painting that goes into Chinese pots and other ceramics. Naturally, we were given lots of time in the large, well-staffed shop before going to dinner upstairs. There were a number of intricately-painted toothpick-holders, but I saw nothing for dental floss.

On the bus-ride back to the hotel, a cryobiologist told me of a modern market in the street north of our hotel. There I discovered the most modern market I ever saw in China. Although the upstairs was a department store with lots of staff and Soviet-style cashier/receipt/clerk purchasing practice, the downstairs was a combination drugstore/grocery supermarket with listed prices, minimal staff and bar-code reading checkout cashiers. The selection was terrific and I took pleasure in the opportunity to study Chinese price levels for foods. Oranges were selling for half the price I had paid. Avocados and quality cherries were priced far higher than what I would pay in North America, but almost everything else was much less expensive. I needed some batteries and was able to buy a package containing six alkaline batteries and a pocket calculator for ¥10.

I was finally told when my 7-day post-conference tour would begin — first thing on the morning of Wednesday, July 21. The conference ended Monday evening so an extra day was left on Tuesday for those who wanted to purchase a guided tour of the Forbidden City. I had seen enough of the Forbidden City, despite only having been there for two hours, so I began planning another day of exploring Beijing on my own.

The first thing I wanted to visit Tuesday morning was the White Cloud Taoist Temple. The Temple was far from a subway stop on the southwest side of Beijing, but I figured that by not being downtown I could take a taxi that would mostly go on the superhighway Ring Roads and not get stuck in traffic. We got stuck in traffic on the superhighways, but the trip was nonetheless much faster than the one I had taken the previous Thursday morning.

Taoism particularly interests me because of the Taoist search for the elixir of immortality, but I found little evidence of that search at the Temple, which was mostly a collection of Temples for the worship of pantheistic statues. There was a Temple of the God of Thunder, a Temple of the God of Wealth and a Temple of the Medicine King (who raised the dead and cured serious diseases). In the Temple of the Jade Emperor I saw a peculiar cone-shaped pillar containing 760 flashlight bulbs, each illuminating a tiny 6-armed Buddha-like image statuette that was numbered and dated.

In front of most of the Temples was a large smoldering container in which worshippers would place their burning incense sticks. Worshippers would kneel before the statues of the various Gods, bow low and pray. The most peculiar statue I saw was the God Defending Taoism. His face was twisted into a ferocious grimace and he held a sword in his right hand, which was held high. His left hand was held forward with the middle finger extended in a gesture that would be familiar to any Western teenager. I saw no other occidentals as I walked through the Temples. I wondered how the worshippers might feel about the unholy presence of a tourist, but no one displayed any obvious concern. The men's room was the filthiest I saw anywhere in China. I used the gutter-like urinal, but did not venture into the defecation area which looked like open pits. At my distance the smell was as much as I chose to endure. There are limits to my desire to sight-see.

I took a taxi to the Xidan market mainly because I had heard of the Cave Heaven restaurant there, which was reputedly built into the underground city. But I failed to find the restaurant. The stores in Xidan were as modern-looking and expensive as any in the world, much too upscale for the likes of me. I spent some time walking along Long Peace Avenue — the grandest boulevard in Beijing, with many magnificent buildings on the north end of the street.

Still wanting to find the Underground City I jumped on the subway and headed to the Chongwen Men (209) subway stop. Walking west on Qianmen Dongdajie street I saw a whole crew of construction workers sprawled-out all over the road taking naps, many still wearing their hard-hats. I find this Chinese alternative to the Western coffee-break to be truly charming. I also came-across a building which had Chinese temple architecture and which in North America I would have taken to be a Chinese restaurant. In front was a huge statue of Bugs Bunny dressed in a Santa Claus suit.

I had a map which indicated that the entrance to the Underground City was on the street immediately south of Qianmen Dongdajie. But immediately south I could only find a dingy alley. My navigation was made more difficult because street names seem to change at nearly every intersection. I walked west along this nondescript alleyway until, to my surprise, I saw a sign that read "Underground City".

Entering the front door I saw about eight young women dressed in miliary garb who seemed delighted to see me. One was appointed to be my guide. I paid a fee (¥20, I think), and was led down a stairway into the cool depths of the underground cave — quite a relief from the sweltering heat of a Beijing summer day. The sides of the cave tunnel passageways were lined with photos of tanks, guns and warplanes. The floor was wet. My guide told me that the Underground City is an Underground Great Wall, and that it can go anywhere in Beijing. It had been built in the 1960s during the Cultural Revolution in a period when Mao was intensely worried about war with Russia. I suspect that much of it has caved-in.

After walking down several tunnels my guide started talking about the advantages of silk in the damp, humid conditions of the Underground City. A tunnel led into a large, well-lit underground silk shop where I was the only customer. She gave me a demonstration of how silk will not soak-up water the way cotton does. To prove the strength of silk, she invited me to attempt to tear a bunch of silk. It was too strong for me to tear. Soon I was looking at silk quilts and being asked which one I wanted to buy. It was a high pressure pitch. The quilts would have been an interesting possession, but it wouldn't fit in my luggage, I didn't need it and I wasn't in the mood to spend ¥1,000 on it. Somehow I managed to extricate myself and depart the Underground City.

I headed east to the Qianmen area to see the largest Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC)

restaurant in the world. Hamburger & bread have not been much eaten in China, so

KFC had a big advantage over McDonald's when it came to getting a foothold in China.

Chicken is a very popular food and China is even shaped like a chicken. The KFC

restaurant seats over 500 people. I took advantage of the public toilets on the second

floor. The toilets themselves were segregated by gender — a toilet room on the right for the

men and on the left for the women — but there was a common area of sinks in the

middle for the washing of hands.

|

I crossed Tienanmen Square to visit the Museum of Chinese History. I had thought I might drop-in on Mao's Mausoleum, but it is closed Tuesday afternoons. On the way to the Museum I was approached by a number of art students, but near the Museum a particularly persistent one walked along side of me and I had a hard time getting rid of him. There was a separate building for storing backpacks in lockers before entering the Museum.

Inside the Museum there was a display of Roman artifacts, but I was more interested in the Chinese exhibits. The Museum reputedly possesses hundreds of thousands of pieces, but only puts a few hundred choice items on display at one time. The items on display were indeed choice. A student approached me and offered to explain the pieces to me. He was a walking wealth of information. I took notes, which I subsequently lost. The main thing I remember is a suit made of 2,000 ceramic squares which had been sewn together and placed on a corpse in a failed attempt to prevent decay. Modern science is mystified as to how the ancient people drilled holes into the corners of the tiles to accommodate the threads. I offered to give my guide a tip, but he refused, saying that he was a volunteer.

I went east and was caught in a ferociously sudden & intense rainstorm. As soon as I got my umbrella open, two Chinese girls crowded next to me to share my shelter from the downpour. The girls giggled & squealed for about fifteen minutes, but the flash flood from the sky was unrelenting and eventually we were all drenched. They thanked me and departed in the rain.

I continued to Wangfujing street for some more shopping. I had been very pleased with some jeans I had purchased at Jeans West for ¥100, so I went back for more. As I was exiting a department store a woman approached me and asked if I would like a foot massage. She seemed like a nice person and my feet were aching, so I agreed to a price of ¥30 for a half-hour massage.

As we went up the escalators to the top floor she told me that I look like a person with a kind heart. I think I was simply too tired to be nasty, but I thanked her. My massage was delivered by a young man after I had soaked my bare feet in a tub of "medicine". He was cheerful & friendly and he had strong fingers. Some of his prodding into my foot was quite painful, but I was assured that it was good for me. The woman sat by my side and chatted with me during the massage. She was an attractive person and I suspected she might be sizing me up as a potential rich occidental husband. Eventually she was asking me if I was rushing off someplace, if I was hungry, if I like roast duck and so forth. But I didn't invite her to a restaurant and when her cell phone rang, that was the last I saw of her. At the counter a clerk asked me for ¥60, but did not protest when I paid the agreed-upon ¥30.

I took a short subway ride to Qian Men (208) to catch up on my e-mail at the Internet Cafe for the last time before leaving Beijing. In my hotel room that evening I carefully separated each waterlogged traveler's check and bill of cash in my money belt and spread them out on the other bed to dry. My passport and airline tickets had been drenched as well. In the future I will be careful to put my valuables in a waterproof ziplock bag within my money belt.

Early (6:30am) Wednesday morning the conference attendees assembled in the hotel lobby to check-out and leave for Xian. Some people were arguing with a clerk that the website for the hotel advertised a rate of $63 per night, whereas the people attending the conference had been given a "special rate" of $80 per night. I too had noticed this, but I could see that the argument wasn't getting very far. I paid for the bill with my credit card, believing that I could have gotten the room for less if I had booked it directly.

The cryobiology conference attendees going on after-conference tours were divided into two groups, the 7-day tour group (my group) and the 8-day tour group. Both groups went to Xian together, but afterwards the 8-day group went east, while our 7-day group went south. The 7-day group consisted of ten people, five of whom were a sub-group from Spain, most of whom did research together. The other five consisted of two married couples of Americans, who had a long history of attending cryobiology conferences, plus me.

Our tour guide told us that we should tip tour guides at the rate of ¥50 per day, and tip the bus drivers half that amount. The suggestion irritated me, but I mostly complied with it for the tour guides. Only once did I tip a bus driver.

On the plane to Xian I sat next to one of the conference organizers, a cryobiologist who

did blood research in Shanghai. Although his reading & writing of English was good, he

felt that the teaching of English pronunciation in China is terrible. I did not have much

trouble understanding him, but I was able to drill him on the pronunciation of

"platelets" (he said "plate-el-ets"). (The letter "L" is not

the problem for Chinese as it is for the Japanese — many Chinese words contain "L",

including "Lee" and "Lu"). In turn, he helped me with questions I had in

my attempts to learn Chinese.

|

After landing in Xian we were taken immediately to the number one tourist attraction —

the terra cotta warriors. Literally, "terra cotta" means "baked earth", and

there are 6,000 of these clay figures assembled in pits to defend the first Emperor of a

unified China, the first Emperor of the short-lived Chin (Qin) Dynasty. The souvenir stands

surrounding the mausoleum are the most numerous and the merchandisers the most annoyingly

persistent of any I saw in China. But beyond a well-guarded line, tourists are able to walk

without having small clay figurines shoved in their faces at every step.

|

The terra cotta warriors were discovered in 1974 when a farmer and his four workers were digging a well. One of the four workers was autographing books in the souvenir shop. He was an unassuming old fellow wearing sandals, shorts and a T-shirt. He was quite a contrast to the titanic mausoleum area and buildings surrounding the pits, which impressed me with their scale more than the warriors themselves. The buildings containing the pits were enormous structures worthy of being hangars for fleets of aircraft.

The warriors had originally been armed with wooden weapons that have

long ago rotted-away. They were also reportedly all unique individuals, individually sculpted,

although this was not evident from the distance of the galleries where we stood looking

down on them. The excavation was clearly still in progress.

|

After seeing the terra cotta warriors we were driven past the old city walls to our hotel downtown. Although Xian was the first capitol of a unified China under the Chin Dynasty, the city walls standing today are remnants of the Tang Dynasty, built when Xian was the largest & richest city in the world. Our tour guide told us that the Tang Palace was five times the size of the Forbidden City.

At dinner we were warned that the foods in Xian can be hot & spicy, like those of Szechwan. I took care to avoid such food, but many of those who did not had stomach-aches the next day. There is much wheat grown in the region, so noodles are the staple of the diet rather than rice (which is the staple in the south). I don't know why there is so little bread.

I did some channel-flipping on the TV in my hotel room and was intrigued by a dialogue

between a minister of the Chinese government and a minister of the government of Israel.

The dialogue was in English (with Chinese subtitles) — another indication that English is

the Lingua Franca of the world. I found the questions & answers

fascinating and it is sad that I remember none of it now.

|

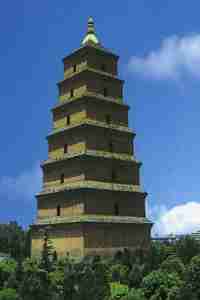

On Thursday morning we went to the Great Goose Pagoda and a nearby museum of historical figures. The museum was something like a wax museum, except the people being represented were not made of wax. There were models of palace eunuchs & concubines showing the traditional dress of the Tang period. One concubine had a red dot on her forehead and another had a blue dot. The red dot was a concubine's way of indicating to the emperor that she was ill or otherwise would not be able to provide good service on a particular day.

Two of the most colorful figures in the Tang Dynasty were women. The Empress Wu had been a concubine, but she was able to use her sons as puppet rulers before setting them aside to have herself proclaimed Empress. Notorious for her cruelty, ruthlessness & tyranny, Empress Wu was nonetheless an ardent patron of Buddhism who favored Buddhist monks as lovers. She also had a hundred male concubines at her disposal.

Lady Yang Kuei-fei was also a concubine, but she didn't need to become Empress to exert power. Reputed to be the most beautiful woman in China, the emperor was ardently enamored, if not bewitched, by her. Lady Yang's cousin was given dictatorial powers, but when war struck the emperor's troops charged the emperor with neglecting his duties. The cousin was killed and the emperor was forced to consent to having Lady Yang strangled to death. The story became a popular theme for Chinese art & poetry.

The Great Goose Pagoda was built as a library to house Buddhist scriptures brought

to China from India during the Tang Dynasty. Our group was given enough time to explore

the premises on our own, but not enough time to climb the tower, which reputedly offers

a magnificent view of Xian. There were a few worshippers, but they were greatly outnumbered

by the tourists. I was particularly struck by one worshipper who I watched burn incense, bow

before the Buddha-image and place a bill in the money-slot. His movements were quick &

mechanical. He impressed me as a busy executive ritualistically manipulating the holy

spirits as a means to his ends.

|

The Xian city walls are the best-preserved city walls in China. The walkway at the top is as wide as a 3-lane highway — triple the width of the walkway atop the Great Wall — and seemed to extend in a straight line as far as the eye could see. The city wall is also quite high, affording an excellent view of Xian — which has 3 million people and many modern skyscrapers. The 8-day tour group departed for the airport at this point, leaving the 7-day tour group to continue exploring the city wall.

Xian was the terminus (or starting-point) of the Silk Routes. So we were taken to an embroidery factory to view the craft. A meter-long silk carpet which would take one person seven months to make could be bought for ¥580. Silk carpets are strong, soft and they change color when rotated due to an effect of light I do not understand. We were given a demonstration of how to tie-dye a silk scarf. When I asked what silk scarves are used-for I was simply told that my wife or mother would know. The woman seemed shocked that I have neither. My observation is that they are decorations for the head & neck. We were given lots of time to shop for silk scarves, carpets, bathrobes, ties, etc., but I didn't buy anything.

We were driven to a hotel for lunch. I stopped by the bus to dicker with a fellow over a pack of postcards he was selling, which I eventually bought for ¥10. But by the that time the group had gone into the hotel. Entering the hotel I saw no sign of them. Finally I got a clerk to locate them on the second floor by calling someone on a cell phone.

In the afternoon we went to the Shanxi History Museum, which reputedly has the best collection of historical artifacts in China. As is common in China, everything was labeled in both Chinese & English. The artifacts were arranged in chronological order, beginning with the skull & jawbone of homo erectus, which had lived in the region 1.15 million years ago. A piece of pottery made 7,000 to 8,000 years ago had been decorated with fingernail marks. There was evidence of what might be the world's oldest written language — written 6,000 years ago — but no one can read it.

To me the most interesting exhibit was the reconstruction of an ancient village. The men all lived in a single hall, but the women all had individual huts, where the men could come visit them. There was a place where all the men were buried and another place where all the women were buried. The women were buried with more artifacts than the men. When a baby or young child died, however, it was placed in a pot near the hut of its mother. The pots had holes in the tops to release the souls of the children.

The souvenir section of the museum was selling packs of postcards at a labeled price of ¥60. When I told the clerk that I had just paid ¥10 for a pack, she belligerently derided the quality of cards sold in the street, but she dropped her price to ¥30. The cards were different enough to justify buying them, but the quality was no better than what I had gotten on the street. I could have argued further about the price, but I paid the ¥30.

We returned to the hotel early, which gave me time to explore the area of the city near the hotel. The map in my guidebook was very sketchy, only having the largest streets named. (Only later did I discover that more detailed maps were available without cost at the hotel desk.) I saw a dairy shop — a rarity given the frequency of Asian lactose-intolerance — and examined the merchandise while the shopkeeper sat silently watching me. I also entered a pharmacy and left immediately when I was questioned in Chinese.

I walked a long time before I saw a street sign at an intersection. Neither of the street names were on my map. I took a right turn and proceeded down a street that had more trees which could shade me from the relentless sun. The shops had no front doors or front walls. They were mostly illuminated by daylight, but I saw an occasional fluorescent light. Many of these shops sold kitchen appliances (gas & electric) as well as gas cylinders.

I finally found a street on my map and was able to orient myself. Walking up the street I noticed a shop selling luggage. I had stuffed my backpack so full that it had torn and I was worried about losing things. I asked the price of a small hardshell travel case and was quoted ¥85. I was startled by the low price, but I must have overpaid because the shopkeeper seemed startled & delighted that I had accepted her first asking price. I'm sure she later resolved that she should have asked for more.

The dinner conversation was dominated by stories from the Americans about being robbed in various places. I learned of the exploits of pickpockets in Paris & Rome. I was most interested by the story of one American man's wife's purse being snatched on a beach in Rio. The husband gave chase to the thief, who ran along the surf pulling items from the purse and throwing them by the wayside, which the wife (who was following) was trying to collect. The chase stopped when the thief threw the car keys (the only thing of real value in the purse). When the man and his wife returned to their spot on the beach, all their belongings were gone.

The wife of the other American man had been missing much of the tour due to aches & pains, which had forced her to stay in her hotel room. She raved about the half-hour massage she had received from the hotel massage service in her room for ¥80. Later I tried calling the massage center myself from my room, but was quoted a price of ¥200 for 45 minutes. I said the price was high and suggested ¥100 for 45 minutes, but they wouldn't negotiate. I went directly to the sauna and saw the price posted as ¥200.

I am a long-time connoisseur of massage — having given more than I have received — so I felt the necessity to experience a full body Chinese massage. I paid the ¥200. The massage was given by a woman who had strong fingers. She massaged me through my clothes — even through my dirty socks. It did not involve much pulling (like Thai massage) or rubbing (like Swedish massage), but used a lot of poking (like acupuncture or Shiatsu) and some pinching (unlike massage I know of). Most of it was pleasant, but some of the poking was painful. I cannot remember whether I felt much better afterward.

Back in my hotel room I placed a long-distance call to North America. I had a calling-card which might have saved me money if I had known how to use it, but my guidebook told me that long distance calls from China are so inexpensive that calling cards are not needed. If this is true, the hotel pocketed the difference because I was charged ¥200 for my half-hour call to the Cryonics Institute. As President of that organization I felt that a phone call would supplement my e-mail in allowing me to keep in touch.

Friday morning we went to the Small Goose Pagoda, another library of Buddhism. The pagoda had the most touching "Keep off the grass" sign I have ever seen: "Please do not trample. Small grass too contain life." The pagoda park had a stage on which a ten-schoolgirl band was playing ancient musical instruments. In front of the stage were rows of the kind of school desks that have broad surfaces on the right arms for writing. Our tour-group and other tourists sat in these seats.

We were given time to shop in a Chinese Art store associated with the pagoda. One of the Spanish women (who had a name meaning "Peace") bought a custom-made birthday card, with her daughter's name written in Chinese characters. (Characters are phonetic as well as symbolic.) A man in the store warned me against wearing my "French foreign legion" cap (which had a hood) because it looks too much like the headgear of the World War II Japanese soldiers. I thought of all the people who might be allowing their necks to sunburn because they don't want to wear a cap that makes them look like a Japanese soldier.

In the afternoon we went to the Great Mosque of Xian, established during the Tang Dynasty in the year 742 AD. Being the end (or beginning) of the Silk Road, Xian has had a sizable Muslim community for well over a millennium. Our tour guide said that Xian Muslims look quite different from Han Chinese, but I couldn't see a difference other than the dress.

I saw more beggars in the vicinity of the Mosque than I saw anywhere in China. And these beggars were as intrusive, insistent & aggressive as any peddlers. They would stand directly in your path and side-step to remain in front you if you tried to side-step. Also surrounding the Mosque was a large market area, selling unusual wares I had not seen elsewhere. I wondered, if airport guards are concerned about planes being hijacked by fingernail clippers & emery boards, how might they feel about a souvenir scimitar? Slices of cantelope with sticks in them were being sold like popsicles. I noticed a McDonalds advertising hamburgers for ¥5.

Xian Muslims face west five times daily when praying to Mecca. I suppose the International Dateline determines whether a Muslim faces East or West, although it is probably not mentioned in the Koran. Few Muslims in Xian can afford the requisite annual pilgrimage to Mecca. The Mosque itself is primarily a very peaceful garden. Only Muslim men are allowed to enter the Great Hall and I was warned to back-off when I stepped within seven feet of the entrance.

From the Mosque we drove directly to the airport to catch our flight to Guilin. Along the roadside I saw a sign that warned motorists "No drunken driving". One of the "treats" we were served in flight was tomato-flavored candy — something I had never seen before.

It was night when our plane arrived in Guilin. With a population of several hundred

thousand, Guilin is a small town compared to the other cities we visited in China. Guilin's

major industry is tourism, thanks to the extraordinary limestone peaks & caves in

the region. My guidebook warned that Guilin subjects foreigners to "a degree of

unrelenting exploitation and extortion audacious even by Chinese standards", but

I experienced nothing exceptional in Guilin in this regard. The gaudy artificial coconut trees

at the airport (which had leaves that flashed

multicolored lights) made me think I had arrived in the Las Vegas of China, but this

too was misleading.

|

Our new tour guide for Guilin had recently graduated from university with concentration in tourism. Her ambitions were to move to Canada and get an MBA.

The next morning when I went for breakfast in our hotel I was told that the upstairs

Western breakfast cost ¥43. I decided to try the Chinese breakfast downstairs,

which came with the hotel room. I found enough edible foods to satisfy me and was

actually somewhat pleased by the culinary adventure, although I couldn't master the

art of eating soft gelatin with chopsticks. The downside was the cigarette smoke. I only saw

3 people smoking out of about 50 patrons, but it was enough to poison the atmosphere.

I have the impression that government anti-smoking campaigns have been far more

successful in China than in Western countries and that Chinese have been quitting in

droves with the same complicity that built the Great Wall. But there are still many

smokers.

|

That morning we went straight to Guilin's premier tourist attraction, the Lijiang River (Li River) boat cruise. Walking out to the dock I spotted a stall selling Chinese peasant hats. I thought this would be a good replacement for my Japanese-soldier cap. My group was moving quickly and I did not want to be left behind, so I quickly haggled the price from ¥60 to ¥50 and made the purchase. We were put on a special boat for foreigners, but most of the passengers were nonetheless of Chinese race.

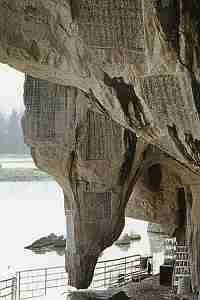

There was a sizable parade of boats on the river, which occasionally felt like a traffic jam. But this was a minor distraction from the scenery. The top of the boat offered a 360º experience of gargantuan shrub-covered rocks. There was a remarkable variety of geological conformations. Sometimes there were shear cliffs against the river. At other times we would be staring across a green plane to a "forest" of limestone peaks in the near foreground. Bamboo trees with fern-like tips often lined the shore. I had lathered myself with mosquito repellent, but I never saw a single mosquito.

After a while we were called downstairs to have our lunch. The Americans sat at one table and I sat with the Spaniards. Although they all knew some English, only one of them — the woman named "Peace" — was really comfortable speaking English. (When they asked about my ability to speak Spanish I demonstrated my ability to count to ten in their language.)

A peddler offered Peace a photo album of Guilin scenery for ¥120. He said he

would write a Chinese poem for her in the book. I was somewhat astonished that she was

accepting the asking price because I had perceived her as being a hard bargainer. I said that

I would pay ¥80 for the book without the poem. We settled on ¥100.

|

Some of us didn't want to waste time downstairs eating lunch, so we each grabbed a banana and returned to the upper deck. For a while we had much more room to maneuver, but soon enough the deck became crowded again. As the boat continued downstream we saw increasing signs of human habitation, whereas initially we had seen none. At one point a couple of men on a bamboo raft came right up to the boat, attached themselves with a hook on a rope tied to the raft, and began to hawk souvenirs. One souvenir was a turtle carved in jade-like stone and another was a Buddha carved in a coconut. The men could just barely reach the bottom of the deck from their rafts, but they did make a few transactions, probably because of the novelty of the situation. Although the men were clothed in little more than loincloth, one of them was interrupted by a call on his cell phone.

I saw a banyan tree that may have been over a thousand years old. I also saw some

water buffalo on an island. Water buffalo swim well, but their meat is extremely tough. Chinese

will eat dogs, but not water buffalo. We were passed by another tour-boat where dishes

were being washed in the back with a clever device which propelled river water in a

rapidly-moving stream into a large basin. It didn't take much imagination to think that the

same method was being used to wash dishes on our boat.

|

There was a large market area on the dock where we were given a half-hour to shop. Our tour guide told us to pay a third of the first asking price and to pretend to walk away from the sale to elicit a better counter-offer, if necessary. I mainly did "sight-seeing" of the merchandise, but when I bought a couple of wooden fans, I was followed & pestered relentlessly by a girl who thought she could sell me another.

We returned to the hotel early, which gave us lots of free time to explore Guilin on our own. I bought a tourist city map at the hotel gift shop and started walking. I stopped at an ATM machine on the street and was pleased to see I could withdraw ¥300 from my credit card. Walking further I came across a shopping mall which was the most dingy shopping mall I have ever seen. It was poorly lit — fluorescent bulbs on the ceiling were infrequent. But what I found incomprehensible was the fact that the mall was entirely devoted to cell phones. Shop after shop — and I must have seen twenty or thirty shops — sold nothing but cell phones. And further down the street I saw two blocks of storefront consisting of nothing but telecom companies.

When I got to the center of the city I stepped into the pedestrian underpass to cross the street and discovered an underground shopping mall. I saw a stall that was selling suitcases and backpacks. The proprietor was having a good snooze. While I was examining the luggage he awakened and gave me a startled look. We bickered a bit about the suitcases and then I started examining different backpacks. Finally we settled on a price of ¥100 for a large suitcase plus a backpack. This was the most personally satisfying transaction I had during my entire trip to China.

I stuck my backpacks in the suitcase and walked back toward the hotel, taking the scenic route along the river. I saw twice as many bridges as were shown on my map. I met our tour guide who was walking in the opposite direction with one of the Spanish men. Our guide invited me to join them on their walk, which I did despite the cumbersomeness of the large suitcase. I told the Spaniard that he could have my smaller suitcase and he happily accepted my gift.

The tour guide told us that the closing of the schools and the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution had set China back ten years compared to other developed countries. When I asked her about her religion, she answered that she didn't have one yet, but that she believes there is a magical force in the universe. When I asked about average income, she estimated monthly incomes of ¥1,000 for Guilin, ¥2,000 for Beijing and ¥3,000 for Shanghai. But she felt that the lower prices in Guilin compensated for the lower incomes. I reflected on the fact that if the ten people in our group each gave her a ¥100 tip, that would give her a month's income in two days. And she works nearly every day during the summer. She said that even the beggars crawling in the streets of Guilin have cell phones. (I never saw a beggar in Guilin.) When I asked why the Chinese TV programs have Chinese subtitles, she said that some people are too lazy to listen to the words. In retrospect I think that the main reason is that Chinese dialects differ, but the script is the same for everyone.

The biggest treat for me during dinner was watermelon juice straight from the cooler.

After dinner I took another trip downtown in search of athletic shoes without shoelaces.

I was looking for Velcro, but couldn't find any except for small children. In one shop I found

athletic shoes without laces that slid-on like slippers, yet seemed to fit tight due to

elasticity. I saw some black ones I liked marked at ¥209. When I indicated that the price

was high, they showed me a white pair which was marked ¥80. They were unwilling to

bicker. I could not see much difference between the black pair and the white aside from the

color. I suspected that having different items marked at different prices was their way of

bickering, while appearing to have fixed prices. I ended-up buying both pairs at their

asking prices.

|